Dependencies and good patches

I think this is a good place to take a little breath and start talking about patches and how to actually create a good history. This can be a tricky task to accomplish but it’s worth it in the long run. Think of your set of patches as little building blocks from which you build a whole project, it’ll help you later when you might want to track down a problem. A cleanly crafted set of patches can be extremely helpful here. Maybe a patch has introduced a bug if the patch is self-contained you can simply rollback that single patch and you can start thinking about a better way to solve the issue than this patch did. Or you can just pick some patches that you are really interested in without pulling in other ones that might currently just interfere with your work.

In this chapter we will take a look at some more details about patches and some thought about how to create good patches.

Dependencies in darcs

First we should take a step back and take a look at how darcs looks at our patches again. Whenever we take a look at our changes with darcs log everything is presented to us in a linear fashion, but that’s not the only way we can think of organizing our patches. We now have heard numerous times that a “repository’s state is defined by a set a changes”. We have also heard what it means when to patches A and B commute, namely that it does not matter in which order we apply them. Until now we didn’t really exploit these properties of darcs that much. So let’s talk a little bit about dependencies so we can get the most out of recording and crafting our patches.

To illustrate how patches can depend on each other in darcs let’s create a very simple repository with two files called A and B. First we are going to add these two files and then we are going to change their contents.

$ touch A B

$ darcs add A

Adding 'A'

$ darcs record -m 'add A' -a

Finished recording patch 'add A'

$ darcs add B

Adding 'B'

$ darcs record -m 'add B' -a

Finished recording patch 'add B'

$ echo A >> A

$ darcs record -m 'change A' -a A

Recording changes in: "A"

Finished recording patch 'change A'

$ echo B >> B

$ darcs record -m 'change B' -a B

Recording changes in: "B"

Finished recording patch 'change B'

patch 376b1bc0febb10802797a5afe7d55e35e42ac89f

Author: raichoo@example.com

Date: Mon Jul 9 19:04:01 CEST 2018

* change B

patch 1f9b4b1566ce3410c70ad5231ff21abb0dfed04b

Author: raichoo@example.com

Date: Mon Jul 9 19:02:49 CEST 2018

* change A

patch 0d87b94c8d03fea3a2b613c43032df8da8cbff93

Author: raichoo@example.com

Date: Mon Jul 9 19:02:02 CEST 2018

* add B

patch 0b2f173ea79d311c34d8e321b6a8d86582d18ff4

Author: raichoo@example.com

Date: Mon Jul 9 19:01:03 CEST 2018

* add ANothing too surprising has happened here. We have added some files and then we have changed them. Everything looks nice and linear. But let’s take a look at how these patches depend on each other.

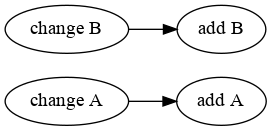

darcs show dependencies will give us some graphviz output that we can pipe into the dot command to generate a visual representation of all the patch dependencies in our repository. The command to do this looks like this.

darcs show dependencies | dot -Tpng -o dependencies-1.pngFor our little example repository darcs and dot will generate a png file that looks like this.

Huh, now that looks radically different. Let’s talk about what this output actually means. We see that change B depends on add B and change A depends on add A. That’s not really surprising. You can only really change a file after you have added it. Makes sense doesn’t it. But how does darcs figure out what patches depend on each other? It’s quite simple. Remember when we talked about commuting patches. To patches A and B commute if we can apply them to our repository in any order and end up with the same result. Now that’s clearly not the case for our patches above. I can’t change a file that isn’t there, therefore I have to add it before changing it. These to patches do not commute, and this is what we call a dependency. You need to satisfy all the dependencies of a patch before you can apply it.

In our dependency graph you can also see that all our changes concerning the files A and B are totally independent from each other. So I could pull only the changes concerning B from the repository while ignoring the changes regarding A altogether. This is an incredibly powerful mechanism that snapshot based version control systems do not have. Now you can pull in a set of patches and ignore all those that don’t depend on the change you are currently interested in. Other version control systems like git for example call this cherry picking, but compared to darcs they are suffering from some short comings. In those version control system you re-record the patch when you cherry pick it. That means that its whole identity changes, one way in which this manifests is that it will get a different hash. So even though it’s the exact same change the patches are now different. This can become quite annoying when working in a distributed setting, with darcs this is a complete non-issue.

Let’s play some more with this. We now want to change file A but let’s pretend that we are referencing something that is in file B (maybe a function, or a paragraph).

$ echo use B >> A

$ darcs record -m 'use B' -a A

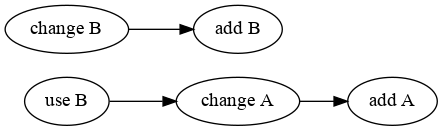

Darn, that’s not really what we wanted. Now we have a change in file A that depends on file B being present, but darcs has no understanding of the semantics of a file’s content. This is problematic because if someone decided to pull in the use B patch without pulling in all our B patches the state of our repository would not make sense. You can’t use anything in B if it isn’t there, makes sense doesn’t it? But fear not, we can instruct record to prompt us for dependencies, so we can inform darcs about semantic relationships between patches. So let’s try again!

$ darcs record --ask-deps -m 'use B' -a A

Recording changes in: "A"

hunk ./A 2

+use B

Shall I record this change? (1/1) [ynW...], or ? for more options: y

Do you want to Record these changes? [Yglqk...], or ? for more options: y

patch 376b1bc0febb10802797a5afe7d55e35e42ac89f

Author: raichoo@example.com

Date: Mon Jul 9 19:04:01 CEST 2018

* change B

Shall I depend on this patch? (1/2) [ynW...], or ? for more options: y

Will not ask whether to depend on 1 already decided patch.

Do you want to Depend on these patches? [Yglqk...], or ? for more options: y

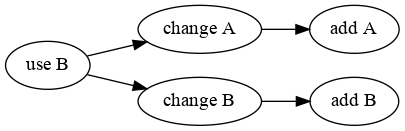

Finished recording patch 'use B'The --ask-deps flag instructs darcs to prompt us for dependencies and we tell it that we want our new patch to depend on the patch change B. Now the dependency graph looks like this.

This gives us unprecedented control over our patches. We now can enrich them with semantic information and our collaborators can leverage that information to mix and match patches to their liking. Want to pull in one feature but not the other one because it’s still too experimental for you, or maybe clashes with some feature you are working on? You can do that now, and all of that while maintaining the identity of patches. This is one of the true powers of darcs.

A thought on patches

I want to talk a little bit about “good practices” regarding patches here. If you are just starting out with version control you might find it hard to figure out what goes into a patch, in the beginning you might start out just randomly recording patches with everything new you have and move along. I’m not going to lie, even for experienced developers, crafting good patches can be somewhat of a challenge.

The most important thing is to try to make patches that make sense. That sounds deceptively easy but this can be a bit tricky. Each patch should constitute unit of work, so if you were to apply it and it’s dependencies, the resulting working tree should also make sense.

So what does it mean for a set of changes in our repository to make sense? In some cases this question is easy to answer in others it’s sadly not that simple. When it comes to a software project, I usually try to make patches and their dependency not break the project. So no matter which patches I pull in, the project should always compile and work as expected. If your project is not code this might become a little harder, like when you are writing a text. If you want to change something throughout your project it makes sense to turn that single change into one patch, here we might think about “making sense” in another way. Like in an earlier example we talked about writing a novel and then renaming the protagonist. A patch that would only perform the renaming on a couple of pages would not be very useful, a better patch would do that throughout the existing parts of the novel. This is a very useful approach because if you change your mind, it gets a lot easier to rollback all of the changes you have decided against.

Writing good patches takes a lot of experience and practice but it’s a valuable skill to train. darcs is a VCS that rewards good patches by allowing you to cherry pick in a way no other VCS can, so striving for good patches is something that you want to keep in mind, especially if you are working with others on a team. Your fellow cooperators will be thankful.

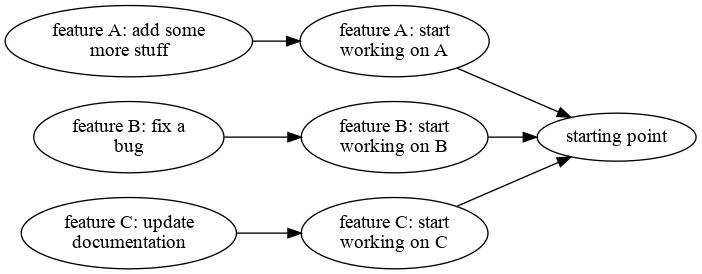

Spontaneous branches

One way where this becomes really quite powerful is something that we call spontaneous branches. If you look at a repository where you are working on a lot of things at the same time you might see a lot of “loose end” in your dependency graph. Take a look at this.

So here you can see a repository where were are tracking the development of 3 different features A, B and C. Since darcs knows about dependencies we can work on each of these features separately without interfering the others. If someone else chooses to work on feature A and we are working on feature B we can do that in a single repository without getting in each others way. Not many version control systems can do that without changing the identity of the patches involved which makes working in distributed teams a lot harder.